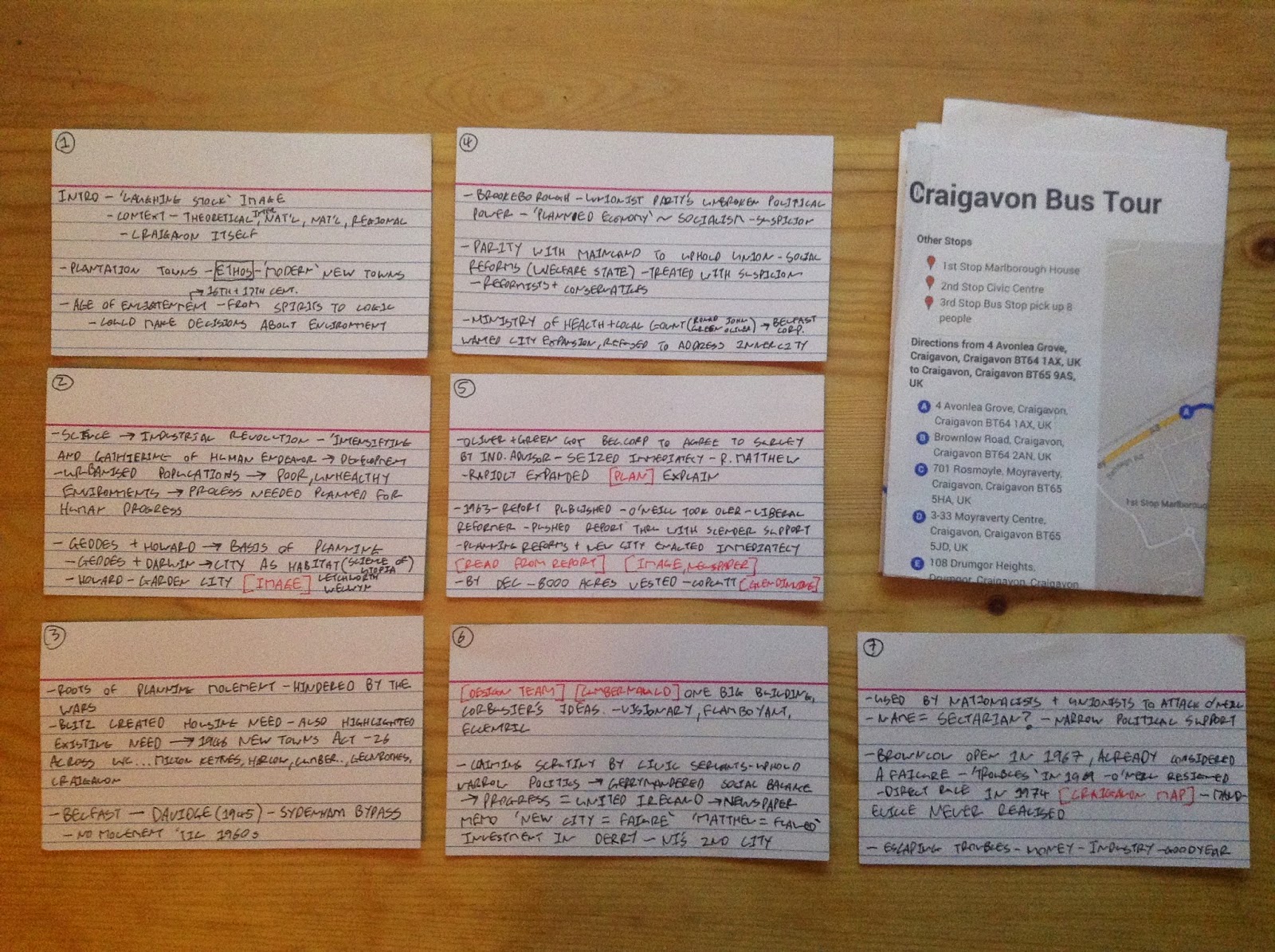

The following are notes made for a bus tour of Craigavon which took place on 1st November 2014. This was part of the Absorbing Modernity series of events based on the themes of the Venice Biennale. The bus tour was organised and hosted by PLACE.

Up until around 3 or 4years ago Craigavon was a bit of black spot in my geographical knowledge of N.Ireland. I found it difficult to get beyond ‘Craigavon as local laughing stock,’ an image which I now see as largely undeserved. I’m going to attempt to explain the broader international context for Modernist new towns and cities and then hone in on the specifically local circumstances which caused and affected the establishment of Craigavon.

Establishing new towns in this part of Ireland of course isn’t a new endeavour, the plantation towns of the Elizabethan era forwards were all described as ‘new towns,’ Modernist new towns however, were based on a totally different set of political constructs. The basis of the architectural and artistic ‘style’ that we call Modernism can trace it’s roots back to the age of enlightenment in the 16th and 17th centuries which saw people starting to turn away from medieval spiritualism and towards reason and rationality and on the back of this came the idea that mankind could begin to analyse, understand and shape it’s environment to improve quality of life rather than being subject to the whims of unseen spirits.

The rise of science then lead to the industrial revolution of the 18th century, which was essentially the intensifying and gathering together of human endeavour focused on the perceived development of society and culture. This lead to increasingly urbanised populations, and with that, increasingly poor, unhealthy and polluted environments in which people lived. By the beginning of the 20th century it became clear that this process needed to be scrutinised and the development controlled and planned to ensure that it contributed to human progress and was not detrimental to humankind.

So at this time you have people like Patrick Geddes and Ebenezer Howard who, at the turn of the century were being to theorise and put forward ideas which proved to be the genesis of what we regard today as ‘planning.’ Patrick Geddes took Darwin’s theory of Evolution to suggest that the city is humankind’s habitat and that, as such, you could arrange it in a scientifically idealised fashion and by way of evolutionary eugenics humankind would evolve to be a more perfect organism. Using these ideas Ebenezer Howard developed the idea of the ‘garden city’ which was an idealised utopia based around several settlements, limited in size, connected by public transport systems and surrounded by greenbelts.

It’s ideals like these which formed the roots of the planning movement across the UK in the first half of the 20th century, all concentrating on attempting to control the development of our cities and, in doing so, ensure that human progress not only continued unhindered but was scientifically guaranteed. Two world wars naturally limited the development of these ideas until 1945, but the Blitz across the UK helped to highlight the poor quality and ageing inner-city Victorian housing stock in big cities including Belfast, but was also, maybe quite perversely, seen as an opportunity by city planners to begin to re-order the cities. The housing need highlighted by the war lead to the 1946 New Towns Act which proposed the creation of 26 new towns across the UK to house the burgeoning UK population.

Belfast had it’s own set of planning proposals, beginning with the ‘Davidge report, commissioned in 1945 which began to look at how the city should be developed. This, however, didn’t really go anywhere apart from an overhaul of the roads system including the construction of the Sydenham bypass in East Belfast. However, the big moment for Belfast and Northern ireland came with the commissioning of the ‘Belfast Regional Survey and Plan,’ commonly referred to as ‘The Matthew Plan’ after it’s author the visionary Scottish architect-planner Robert Matthew. This came at the end of Lord Brookeborough’s 20 year stint as Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. The Unionist party had held unbroken political power since the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 and had done so by strictly adhering to their strict conservative values. As such they opposed anything which vaguely resembled socialism, and the concept of planning was considered to be connected to the communist ideals of a ‘planned economy.’ So these ideas were treated with deep suspicion.

The policy of ‘parity’ with the mainland, while seen as being important to uphold the union, started to unravel slightly as social and economic reforms such as the establishment of the welfare state came into being, these being socialist ideas. Things like this started to create rifts within the Unionist party as two distinct camps, conservatives and reformists, began to emerge. The newly stablished Ministry of Health and Local Government was firmly under control of the reformist camp, including the young and innovative ministers Ronald Green and John Oliver, began to put pressure on the conservative Belfast Corporation who were opposed to inner-city slum clearance coupled with public housing schemes. Oliver and Green managed to back Belfast Corporation into a corner and forced them to agree to allow an independent adviser to come over and assess the housing problems in the city. The ministers immediately contacted Robert Matthew, this was in 1960, an experienced architect-planner from Edinburgh, to put together a report on the development of Belfast. This report quickly expanded into a full ‘regional survey and plan,’ looking not just at Belfast but at Belfast in it’s region as the economic centre of Northern Ireland.

The plan itself proposed a hard stopline around Belfast to stop it’s sprawling outward expansion. As the population of Belfast was increasing exponentially the stopline limited this, so several towns in the region were designated to be redeveloped to deal with what was referred to as the ‘overspill’ of population. These expansion towns would ‘demagnetise’ Belfast. A newly established motorway system, which was already on the table, would allow people to commute in and out of Belfast for work, while new industries would also be established in the expansion towns. At the same time, a new city was to be built between Lurgan and Portadown.

FROM THE "MATTHEW REPORT"

LURGAN/PORTADOWN: A REGIONAL CITY - It is proposed that the existing towns of Lurgan and Portadown be expanded into a substantial new city of approximately 100,000 people, this being the most important single new development suggested in the Plan. These two towns, with existing populations of 18,667 and 17,873 respectively, are three miles apart and are selected for major expansion for the following reasons.

- Their location beyond the head of the Lagan valley is in the natural direction of development into the hinterland and close enough to Belfast to attract industrial enterprise.

- They have good rail connections with Belfast and the south and can easily be linked, by road to the proposed Belfast-Dungannon motorway (M1). Their proximity to Lough Neagh could take advantage of water transport, should it develop on the largest stretch of inland water in the British Isles.

- The configuration of the land is well suited for building. It is not of first class agricultural quality, but has a ready availability of utility services, such as water and electricity.

- The existing urban centres have established populations and reasonable existing social and commercial facilities which would make a sound base for expansion.

The proposal, which it is important to regard as of first priority, is to create a major new urban area for administration, industry, marketing, technical education and recreational activities. It presents an opportunity to create a contemporary urban environment of high quality, which could serve as a major symbol of regeneration within Northern Ireland.

In 1963, the year the Matthew Plan was published, Lord Brookeborough stepped down as PM due to health reasons and Terrence O’Neill took over. This is important because O’Neill was very much in the reformist camp. He therefore fully supported the distinct social edge of the Matthew report and the proposed planning and housing reforms albeit without significant support from the staunchly conservative Unionist party. O’Neill managed to push through the majority of the reforms to the planning system including the stopline, along with the establishment of the new town, at break-neck speed, to the degree that the new city planning team was established barely a month after the report being published.

By December that year 8000 acres of largely agricultural land between Lurgan and Portadown had been vested and the highly influential ‘new city’ architect Geoffrey Copcutt was given the job of leading the new city design team. The following was taken from Miles Glendinning's 'Modern Architect,' an excellent biography of Robert Matthew.

During 1964, Copcutt's team had completed a preliminary report on the new city, which, when eventually published, proposed a basic structure like a more dispersed Cumbernauld, with a 'linear urban core,' strongly set apart from the countryside around by a ring distribution road, and individual zones containing fairly dense 'clusters' of compact residential 'sections' - each with its communal facilities (such as schools) grouped at the centre, implicitly intended to encourage Catholic-Protestant integration. These would be interspersed by three commercial centres: Lurgan, Portadown and a new regional high-grade shopping and office centre between.

Copcutt became increasingly frustrated with Stormont politics, claiming that his designs were being scrutinised by civil servants to ensure the subtly gerrymandered civic balance wasn’t being upset. He even went further suggesting that the best way to allow Ulster to progress was to have a United Ireland. In August 1964 Copcutt send a memo to several major newspapers in N.Ireland decrying the new city project as a failure before it started and claiming that the Matthew Plan was seriously flawed. He suggested that the money being used to develop the new city should be used to invest in N.Ireland’s current second city, Londonderry, and that the decision not to do so was political, sectarian and demonstrated O’Neill’s blind adherence to the Matthew plan in the absence of any political support. Copcutt immediately resigned, mere months after being appointed. Copcutt's memo was used by Nationalists to claim O’neill and the Matthew Plan were sectarian constructs, while the conservatives within the Unionist party used it to claim that the Matthew Plan and the new city were socialist constructs. Another furore was sparked when the new city was named Craigavon, after NI’s first prime minister. O’Neill’s political support was getting ever smaller.

By the time residents moved into Brownlow in 1967, the first of a proposed three housing estates in Craigavon, the entire project was already viewed as a failure.The onset of the ‘Troubles’ in 1969 also put a firm end to Prime Minister O’Neill’s liberal experimentation and he resigned. As we now know the political system in NI unravelled over the next 5years resulting in the imposition of direct rule in 1974. Meanwhile the ‘failed’ new city of Craigavon went through it’s own set of trials and tribulations. First of all, not enough people moved out, but with the escalation of the Troubles and the corresponding deterioration of inner-city Belfast, young families trying to escape the violence were attracted to the city. Additionally, new citizens were given an initial amount of £250 to move out, later bumped up to £500. On paper it was an allowance to furnish a new house but is thought by many to be vulgar bribe.